Beating the Open Shop, The Early 1900s: Part 1

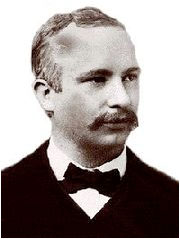

During the twenty-one years of McGuire’s stewardship, the UBC succeeded in setting union standards for most carpenters on most construction sites in the U.S. The struggle to achieve these goals was long and difficult. Building contractors used all the tools that employers have typically adopted to drive away unionism—strikebreakers, blacklisting, yellow-dog contracts, and violence. Long after the UBC had established a firm foothold in the industry, contractor associations continued to attempt to undermine the union’s power.

In the first decade of the 20th century, an aggressive nation-wide open-shop attack was mounted against the carpenters’ union. Employers locked out union carpenters in Chicago, New York, Pittsburgh, Louisville, Houston, Milwaukee, and a number of other cities. Frank Duffy, the General Secretary who succeeded McGuire, wrote in a 1904 issue of the Carpenter that building employers had “organized, combined and affiliated with one another, with the avowed purpose and firm determination of putting our local unions out of existence altogether.”

Yet, despite the bitterness of the conflict, the peculiar characteristics of the construction industry made organizing turn-of-the-century carpenters a possibility at a time when many other sectors of the workforce were unable to break through the barriers of anti-unionism.

In 1900, as the Brotherhood was rapidly expanding, no more than 6 percent of the manufacturing workforce was organized—and that group consisted almost exclusively of the small number of highly skilled operatives whose craft had not been diminished by the factory system. The difference between the organizing potential of factory vs. building trades workers is illustrated by the comments of employers in each field. In an era when a U.S. Steel executive could boast: “I have always had one rule–if a workman sticks up his head, hit it.” Otto Eidlitz, one of the nation’s most powerful builders, proclaimed, “It is without question not only the right but the duty of labor to thoroughly organize itself and it. . . is a power of good in the trade.”

The differences in viewpoints were not due to the benevolence of construction employers. Rather, the economics of the industry encouraged fair-minded builders to reach an accommodation with the unions. Short on capital and dependent on monthly progress payments, small and medium-sized contractors were unable to stockpile resources to withstand the financial strain of a long strike. Furthermore, the highly skilled nature of the work made it difficult for anti-union employers to quickly replace competent carpenters with capable strikebreakers. As a result, builders who were faced with the power of a militant and popular union ultimately chose to forego endless battles and instead accepted agreements with local unions.

Additionally, many building employers recognized the potential benefits that unions could provide in terms of apprenticeship training and hiring hall. In a highly volatile industry with boom-and-bust cycles, employers had difficulty making long-range plans with regard to labor requirements. To the extent that unions willingly accepted the responsibility of training and supplying labor, contractors were relieved of a difficult burden. From their perspective, the positive role of the unions often outweighed the added costs of union recognition and above-average wages in the construction field.

The conditions in the industry thus laid the groundwork for McGuire’s brand of democratic and activist unionism to flourish in the late 1800s and early 1900s. Despite the intensive efforts of open shop employers, membership in the Carpenters’ Union reached 200,000 by 1910. A union card became as crucial to a self-respecting carpenter as a complete set of tools. For those who knew the industry, it was a matter of common wisdom that, “the craftsman without a card is a man without a trade.”

McGuire’s successors–Frank Duffy and William Hutcheson (who, as General President, presided over the Brotherhood from 1915 to 1951)–altered the union’s orientation. Less intent on carrying out McGuire’s motto of “organize, agitate, educate,” they emphasized the smooth administration of the union operation.

Less interested in McGuire’s philosophies of social change, the UBC under Hutcheson took on a more conservative political cast. More skeptical of broad working-class movements, Hutcheson’s Brotherhood staked out a tougher position in a relation to other labor unions in and out of the building trades. Conflicts over jurisdictional assignments became one of the primary methods of extending working carpenters’ interests.

McGuire recognized that the turmoil in the construction industry made conditions ripe for the organization of carpenters. If the carpenter’s trade was under attack, there was only one appropriate response—protect and defend the trade through the collective action of its members. The delegates who gathered in Chicago acknowledged his leadership as a crucial element of the union’s potential for success. While they could not resolve all the debates over the issue raised at the convention, there was no disagreement over who would fill the one full-time position. McGuire was unanimously elected to the post of General Secretary.

McGuire recognized that the turmoil in the construction industry made conditions ripe for the organization of carpenters. If the carpenter’s trade was under attack, there was only one appropriate response—protect and defend the trade through the collective action of its members. The delegates who gathered in Chicago acknowledged his leadership as a crucial element of the union’s potential for success. While they could not resolve all the debates over the issue raised at the convention, there was no disagreement over who would fill the one full-time position. McGuire was unanimously elected to the post of General Secretary.

McGuire recognized that the turmoil in the construction industry made conditions ripe for the organization of carpenters. If the carpenter’s trade was under attack, there was only one appropriate response—protect and defend the trade through the collective action of its members. The delegates who gathered in Chicago acknowledged his leadership as a crucial element of the union’s potential for success. While they could not resolve all the debates over the issue raised at the convention, there was no disagreement over who would fill the one full-time position. McGuire was unanimously elected to the post of General Secretary.

McGuire recognized that the turmoil in the construction industry made conditions ripe for the organization of carpenters. If the carpenter’s trade was under attack, there was only one appropriate response—protect and defend the trade through the collective action of its members. The delegates who gathered in Chicago acknowledged his leadership as a crucial element of the union’s potential for success. While they could not resolve all the debates over the issue raised at the convention, there was no disagreement over who would fill the one full-time position. McGuire was unanimously elected to the post of General Secretary. In August 1881, 36 carpenters from eleven cities met in a Chicago warehouse to form a national union. Four days of heated discussion produced a constitution, a structure, and a new organization with two thousand members—the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America.

In August 1881, 36 carpenters from eleven cities met in a Chicago warehouse to form a national union. Four days of heated discussion produced a constitution, a structure, and a new organization with two thousand members—the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of America.